.png)

As an immigration attorney, I’ve learned to expect that immigration law will be complicated. I’ve learned to explain uncertainty to clients. I’ve learned how quickly policies can shift beneath our feet.

What I still struggle to accept is this: an asylum seeker can spend years in the United States doing exactly what the system asks of them: filing an asylum application in good faith, appearing for each hearing, following work authorization requirements, and building a life while their case moves slowly through the docket—because the government has told them, explicitly, that they will have a chance to present their claim.

Then, one day, they stand in immigration court and hear an ICE attorney say something like: “The United States has an Asylum Cooperative Agreement with Honduras. We ask that the court terminate these proceedings and order the respondent removed to Honduras today.”

In that moment, the process can feel less like an individualized adjudication and more like a procedural shortcut: no hearing on safety, no meaningful opportunity to test the premise, and no clear mechanism to explain why this person, in these circumstances, should be sent to that specific country.

Just like that, years of reliance on the system can seem to evaporate.

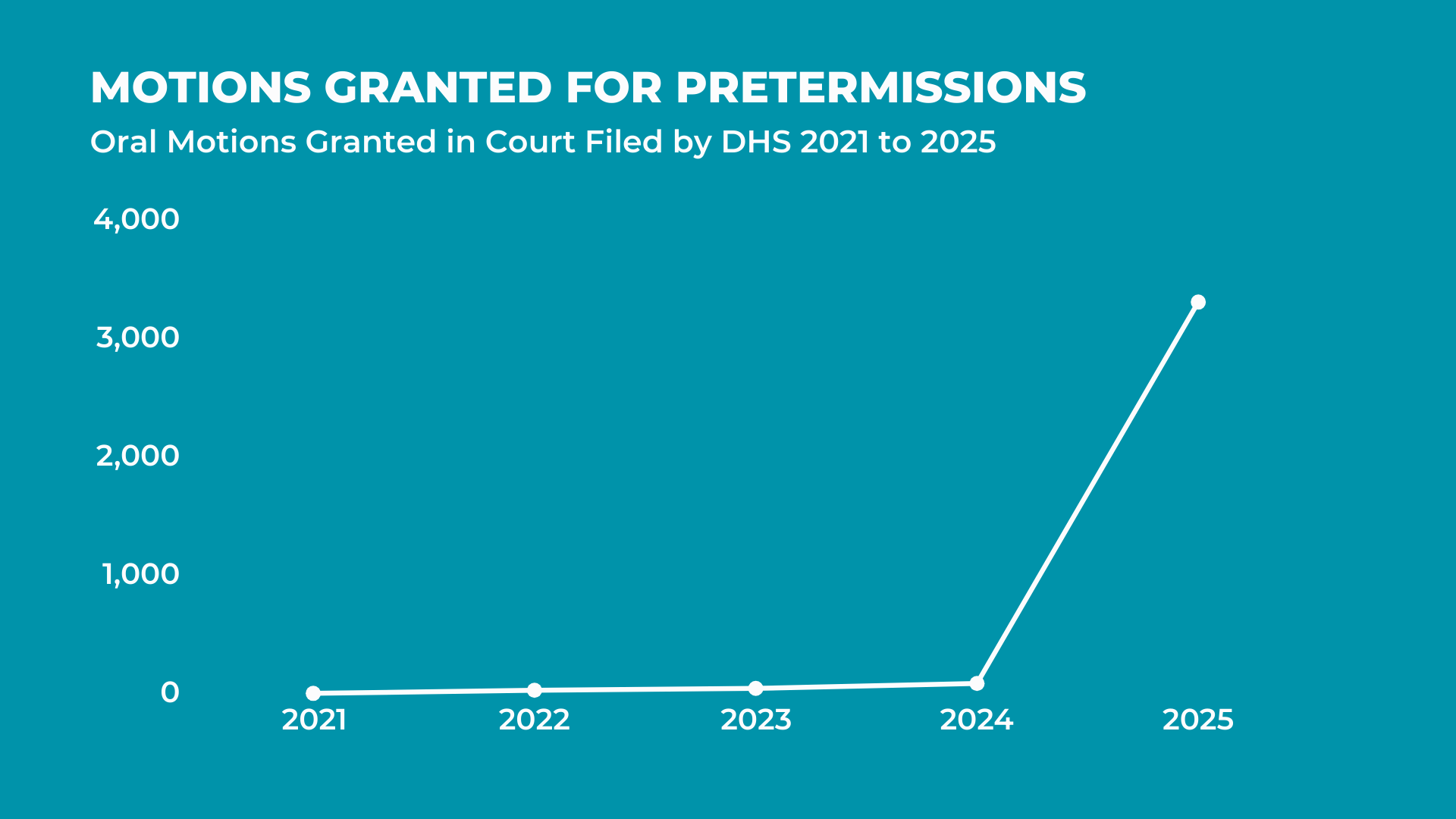

At Mobile Pathways, our data shows that pre-termination (pre-term) motions tied to third-country removals have surged (notably sharply in December) as shown in the graph below. Based on our validation methodology, the most likely explanation is an increase in cases being redirected through Asylum Cooperative Agreements (ACAs), a legal mechanism the government frames as a “third-country transfer.”

An Asylum Cooperative Agreement (ACA) is a bilateral arrangement under which the United States asserts it may transfer certain asylum seekers to a partner country to pursue protection there instead of having their asylum claim heard in the U.S. For more on the most recent agreements

In practice, the government treats the transfer as a form of third-country removal, on the premise that the receiving country’s asylum system is available and that the person can seek protection there (subject to whatever exceptions or screening procedures the program provides).

One of the most troubling aspects of these Asylum Cooperative Agreements (ACAs) is how they constrain judicial review.

The executive branch (through the State Department) has already certified that certain countries have “safe and functioning” asylum systems. That certification is then treated as settled fact in immigration court. As a result, immigration judges are often not permitted to meaningfully examine questions that should be central to any asylum determination:

The legal fiction is that these questions have already been answered at a diplomatic level. The reality is that the person in front of the court bears all the risk if that fiction collapses.

If this framework is fully implemented, it threatens to hollow out asylum without ever formally repealing it.Under this approach, an asylum seeker must now show that they are more likely than not to be harmed in a third country they have never lived in—on one of the narrow, legally recognized grounds in asylum law.

As an immigration attorney, I will tell you that is an almost impossible evidential burden.

How do you prove future persecution in a country where you have no history, no documentation, no social ties, and no record of past harm?

You don’t.

And that is precisely why this framework is so effective at denying protection while preserving the appearance of legality.On paper, asylum still exists. In practice, the door is quietly being closed.

.jpg)

There is a point at which legal removal starts to resemble something far more severe. Sending someone to a country where they have no family, no community, no legal stability, and no guaranteed safety is not simply a neutral administrative decision. It is a forced uprooting that most Americans would never accept for themselves or their children.

As lawyers, we’re trained to strip cases down to elements and standards. But standing in court, watching someone absorb the reality of being sent to a place they’ve never known, it’s impossible to ignore the human cost.Too often, these agreements are discussed in the language of acronyms and policy memos: “ACA,” “third-country processing,” “alternative protection pathways.” In the courtroom, however, the shift can happen in a matter of minutes—government counsel makes the request, a judge’s discretion is limited, and a case that has been pending for years is suddenly rerouted.

For the person at the podium, that moment can feel like the collapse of what they were told to trust: the chance to be heard, the stability of a pending case, the belief that following the rules mattered.

Immigration law has to be rigorous, yet it also must be be forthright about what the law is doing to people.

When a system invites reliance over years and then ends the process without a meaningful opportunity to respond to the basis for transfer, the result may be lawful on paper, and still feel deeply punitive in practice. These are not abstract policy experiments.

They are lives redirected through agreements most people never see, to countries they have never known.