Almost every industry relies on real-time data to make decisions in 2025. Live stock data, latest social media posts, or what items are in your Amazon shopping cart are common inputs into various algorithms that impact what we see online and the choices we make.

In our work at Mobile Pathways, we often don’t have the luxury of working with data that is hot and fresh or refreshed on demand. Our Immigration Court Data hub gathers information and insights from a variety of sources, published at different times and cadences, with differing levels of quality and accuracy. Our scrapes and aggregations are tenuous at the best of times, held together with scrappy code that gets tweaked every time a source updates.

What happens when our #1 source on deportations, ICE, USCIS, and immigration courts goes dark for two months?

.png)

When agency workers are furloughed and no one is left to provide regular refreshes of critical datasets, our work is directly hamstrung. The longest government shutdown in history severely limited how we could monitor and assess what was happening in immigration court, even as tens of thousands of asylum cases were decided throughout September and October. This blackout left our partners– advocates, attorneys, and nonprofits – flying blind, raising serious concerns about what was happening.

We heard a variety of rumors from those within the court system and from journalists who were trying to get a handle on latest trends. In an ecosystem where new policy memos released today begin to have an impact on cases tried tomorrow, the delay in information left us unable to verify what was fact from fiction or help answer questions on what the practical implication of new rulings have on upcoming cases.

The lights are back on, but the view is terrifying. Our key data sources have returned, and the new trends are alarming.

.png)

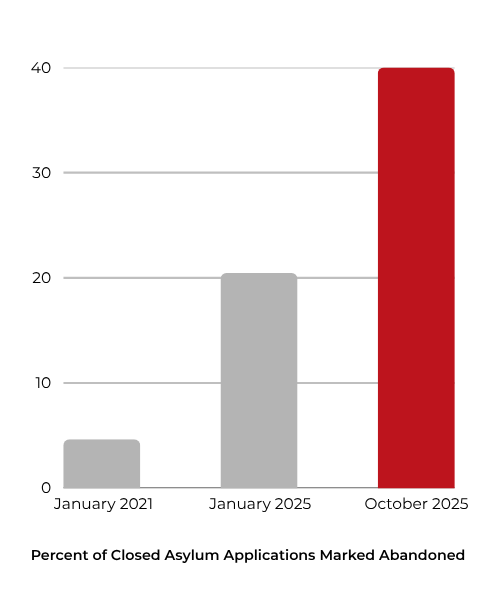

According to the Executive Office of Immigration Review (EOIR), abandonment is an outcome for applications on file that have either a major deficiency or the applicant was untimely in responding to a request during the application process. This can include failure to appear for a hearing. While this has always been an outcome within the dataset and is not something new, it has historically been used sparingly.

At the beginning of the Biden Administration, only 5% of closed asylum applications were marked as abandoned. By the start of the second Trump Administration, that number has jumped to 20%. Over the last month, the total number of abandoned applications increased again to reach 40% of all outcomes– on par with the total number of applications being denied.

This increase in abandoned applications is happening across the entire nation. It isn’t limited to one court or a cluster of judges, though the increases are more noticeable in some locations than others.

In Atlanta, the abandoned rate has climbed to 56%.

In San Antonio? 64%

And in Salt Lake City, Utah– a whopping 73% of cases where marked abandoned in October alone.

We recently hosted a webinar with former Immigration Judge Ilyce Shugall to unpack what these trends mean in practice. While the story is still developing, there is broad consensus among experts that the data is alarming—from the rise in “voluntary” departures to a troubling surge in in absentia deportations. Joined by Jeffrey O’Brien, Ana Ortega-Villegas, and Bartlomiej Skorupa of Mobile Pathways, we walked through fresh court data that sheds light on the urgent challenges immigrants now face in court.

When stumbling in the dark, it is hard to know what is going on around you. And even with our access to data turned back on, the light is dim when our best data is lagging indicators that are often 30 days delayed. For timely and responsible advocacy work and supporting those who are in court each day, we need to improve the flow of data and ensure we can main transparency on the process. Reliable and consistent data that is as up to date as possible is mission critical for everyone keeping eyes on immigration court, from journalists to nonprofits to industry associations like AILA or NAIJ.

Data is a common good. As citizens and practitioners of the court, it is imperative that this information continues to flow.

Our work, the work of our immigration partners, and the work of the thousands of individuals and organizations who are working alongside asylum seekers navigating immigration court every day desperately relies upon it. Fair access to justice relies upon it. And if we cannot trust the government to uphold its responsibility to provide accurate and timely data, we may as well go back to sitting in the dark.